Editorial Posted by Siru Heiskanen on September 11, 2017

Biophilia – The Love of Life and All Living Systems

From a genetic standpoint, we are hunter-gatherers from 40,000 years ago: our biology hasn’t much changed from it.

We are meant to live in nature.

Imagine you are outdoors. The sun is glistening from the surface of a lake, and it’s silent except for the sound of a warm breeze shaking the leaves of a forest surrounding you. Take a moment to breathe.

How do you feel? Calm? Happy?

These positive emotions we connect with nature cause us to seek its presence: taking a walk in the park, bringing plants indoors, preferring a window seat. When people are asked to list their favorite places, natural environments are over-represented and likewise underrepresented among the unpleasant places (1).

This concept for our instinctual desire for nature is known as biophilia. While the term is not too well-known, the concept is still very pervasive: people are willing to pay higher prices for real estate closer to lakes, beaches and parks, for high-rise views over cities and forests, or a mountain vista.

Why is it that we are so driven towards nature?

And why do especially some features, such as water and plants, have such a great impact on our mood and emotions?

Movies leverage this reaction for the purpose of leading the audience. Placing protagonists into dry terrain and cities without visible vegetation often indicate the audience that the hero is in a hostile environment. Similarly, antagonists tend to base their operations in sterile, concrete bunkers while protagonists often prefer garden-like places with running water.

The strongest messages are inwritten

A vast amount of scientific literature has shown that nature has a fundamental positive influence on our minds and bodies, and scientists from different fields have taken the task to figure out the mechanisms behind this phenomena.

The concept was named by an influential biologist Edward O. Wilson, who is also known for coining the term ‘biodiversity’. The name is derived from the Greek words ‘bios’ (organic life) and ‘philia’ (one of the four ancient words for love).

Wilson proposed that contact with nature is a universal, basic human need derived from our evolutionary history.

Our ancestors living in the African savannah evolved to prefer certain kinds of features in their environment, including a high diversity of plant and animal life for food and resources, high vegetation for refuge and protection, and elements of water for drinking and bathing. It is no coincidence that many of the natural features which today are found to be aesthetically pleasing were also crucial for the survival of our species.

Surroundings change – instincts stay

São Paulo (Brazil) and Tampere (Finland).

Denser population sometimes comes with drawbacks, as space for nature to flourish is lost.

Now, as the landscape of the Earth changes more rapidly than ever due to human influence, it has become more important than ever to understand the relationship we have with nature. Even though we are capable of adapting our behaviour greatly in order to thrive in our modern environments, our brains and physiology are inherited from the ancestors who evolved in very different conditions.

We carry the traits that made the survival possible for them, and there is no doubt that it influences our psychology and physiology to this day.

The concept of biophilia is unfamiliar to many of us, but its basis is easier to understand if we consider it backwards: the most common fears humans and animals have are related to nature. Snakes and spiders, for example, might not be the most relevant fears to have when living in urban environments, but still they remain. Fear is a powerful response to situations or stimuli that could potentially be harmful for us or pose a threat to our survival, and because of its evolutionary significance, fears are highly heritable.

Our innate need for nature

Just as evolution drove our ancestors to avoid natural stimuli that indicates danger (biophobia), advantages provided by specific features in the surroundings could have been so central to survival that natural selection favored individuals who responded to them by approach (biophilia).

Biophobia and biophilia.

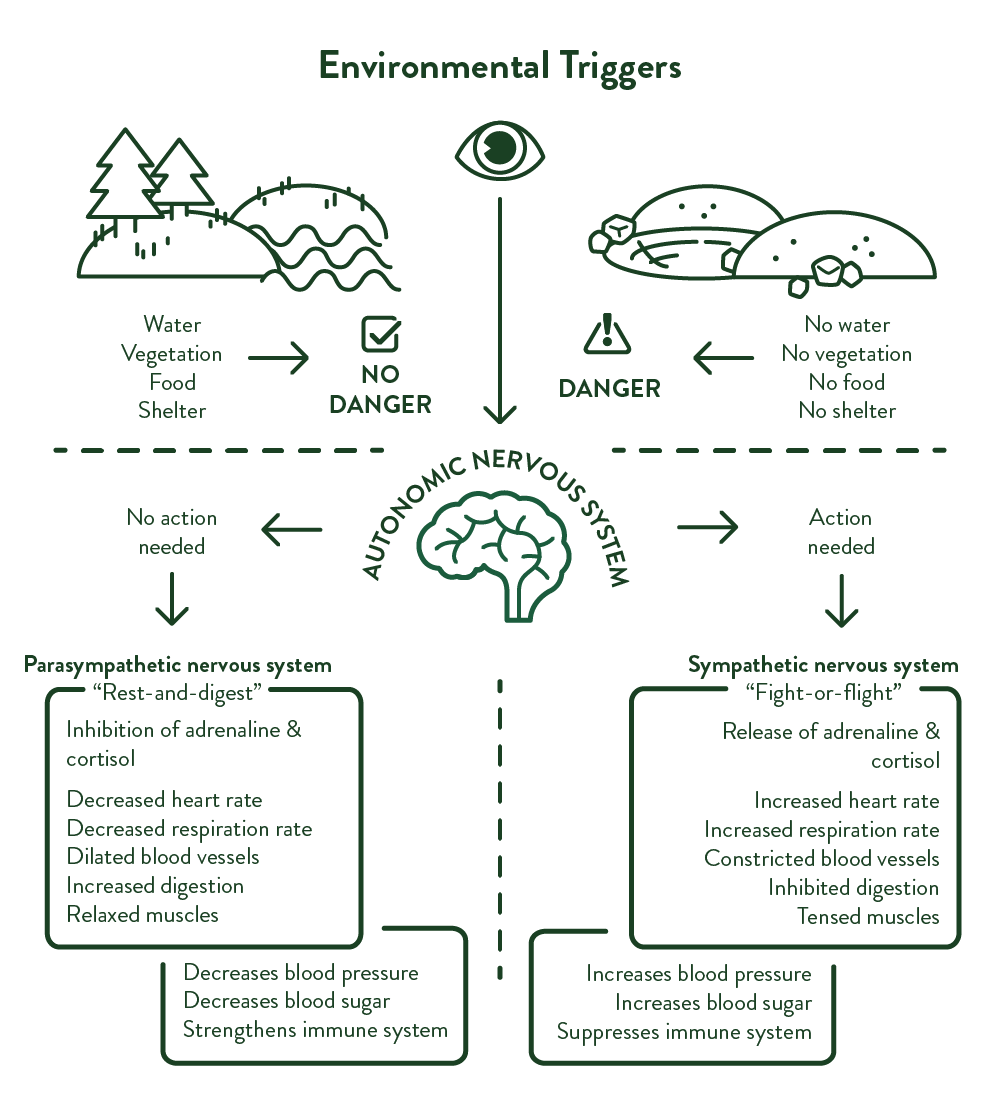

Fear is often associated with acute situations such as facing a dangerous animal, but our physical environments can also differ regarding to their risk and survival properties. When we face something we are afraid of, we experience a physical reaction: our heartbeat and breathing hastens, muscles tensen, and our digestive processes slow down. This is caused by activation of our sympathetic nervous system, and is know as the “fight-or-flight” or acute stress response.

By releasing adrenaline and cortisol, we prepare ourselves for challenging situations as they increase our physical readiness. Together with the “rest-and-digest” reaction of the parasympathetic nervous system, our autonomic nervous system keeps a balance between stress and rest. Frequent or chronic activation of the stress response, however, can result in physiological wear and tear. Common causes for chronic stress derive from our modern environment and fast paced lifestyle, both of which can be psychologically demanding.

Environmental triggers of Biophilia (click image to enlarge).

Environmental stimuli triggers physiological and psychological responses in our body in order to behave in the most beneficial way according to the situation. Environment that is lacking features essential to survival triggers our sympathetic nervous system to cause behavior that will lead us to a safer environment. Our modern habitat is often lacking the visual cues - water, vegetation - which tell our brains it’s okay to relax.

The restorative power of nature, scientifically proven

Stress often drives people to seek relief through nature, even though we might not understand the biological basis for it. It is our innate desire to seek a safe environment that is behind the feeling of calmness and happiness caused by nature, which allows our bodies and brains to restore and maintain their energy. This is called the stress recovery theory (SRT). Due to this restoring effect, we are also capable of performing better on tasks that require our directed, voluntary attention.

Directing our attention to a task that is inherently boring (meaning, not that important to our survival such as looking out for predators) requires concentration. This is easier for us when our surroundings support our directed attention instead of making our involuntary attention to drift. This is called the attention restoration theory (ART). Vast amount of research supports SRT and ART, backing up the biophilia hypothesis.

Contact to nature has three different classes:

- Outdoor nature contact.

- Indoor nature contact (i.e. view from a window, natural light, living plants).

- Indirect nature contact (i.e. photographs of nature, recorded nature sounds).

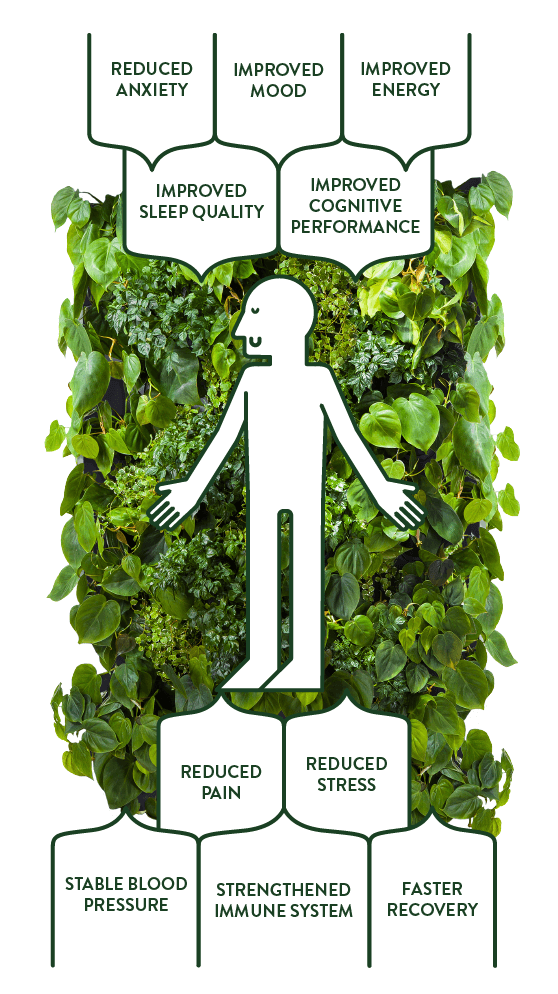

All of these ways to connect with nature have been linked to health and well-being, direct connection most strongly, and indirect connection the least. Exposure to natural elements is known to e.g. reduce stress and anxiety, improve mood, energy levels, sleep quality and cognitive performance, decrease blood pressure, maintain stable blood sugar, aid in faster recovery, inhibit pain, and strengthen the immune system (2).

Biophilic design: Bringing nature indoors

By spending more and more time indoors, we risk isolating ourselves from nature. The issue is not only about losing contact with a range of flora and fauna: buildings define how much we are exposed to noise, temperature, and their changes. Through lighting, buildings also affect our circadian rhythm and therefore our alertness.

When constructing buildings, we often consider investing in real estate, land, and technology instead of the actual purpose of the buildings, which is for people to live, work, learn, and recover in them. Avoiding health and safety risks comes as a given, but a healthy environment is one in which there is not only an absence of harmful conditions but an abundance of health-promoting ones.

The more our modern environment includes the elements we innately consider important, the more it will support us psychologically, emotionally, as well as functionally. Incorporating nature to our urban planning is called biophilic design.

3 tips for biophilic design

Below, we have listed some quick ways of implementing biophilic design. Remember that direct contact with nature is always better than indirect contact or contact with artificial plants. However, any form of contact is better than none at all.

1. Bring in the light

Light affects our circadian rhythm, and can therefore have a major impact on our alertness. Not only does it tell our bodies when to wake up or go to sleep, but it also controls the release of some hormones that take care of our energy levels. Biophilic lighting has been proven to improve the quality of our sleep, too (3). Sunlight through windows has also been linked to general wellbeing, health, and even job satisfaction (4). Artificial blue light from screens, phones and tablets can disrupt our sleep, making us tired, and can cause headache and eyestrain.

2. Soundscape

Simply opening a window may do - if you are not located in an urban area where the only sounds are traffic and the hectic city life. In that case, it might be better to ensure proper soundproofing from outdoors. Instead, adding elements with the sound of flowing water could improve the sound scenery indoors. Recorded sounds of nature work too!

3. Visual contact

Visual connection with nature can be incorporated indoors in many ways: a view from a window, pictures of nature, or houseplants. The more plants, the better. One of the most space-effective ways to add green indoors is via vertical green walls. They can also act as room dividers to create more privacy, and improve the acoustics by reducing echoing. There is a vast amount of research showing the many benefits plants indoors can have on us, from physiological to psychological well-being (5).